What is the difference between a product and a service? Anymore, physical products are supported by a vast array of services, from the "seen" - like optional VIP support packages - to the unseen, like automatic software updates delivered in the wee hours of the morning. Likewise, services are "packaged" and priced like products, perhaps the most diabolical of all being the 2-year mobile voice/data plan - with which you often get your choice of "free" phones (a physical product) that is in reality an incidental delivery device for the premium-priced service.

How do you know when you've reached a minimally viable product? What is a rational method for prioritizing critical (essential) design requirements? What are good definitions to make clear the responsibility of product marketing versus product management? (Where) do they require consensus? What is the biggest product-specific challenge when scaling an operation? What part of whole product marketing provides the greatest ROI in terms of customers being satisfied that their expectations were met?

Answers to these questions and other PRODUCT lessons learned, real-world examples, and best practices are recounted here.

I tell people who are interested in designing products to just get started. Start small; start with something that is achievable and possible. While everyone may have a picture in their heads of what the final product could be, that’s not where you start. Just put something out there. It doesn’t even have to be great, as long as it helps you evaluate the need for what you are trying to accomplish.

A perfect example is Zappos. Tony Hseih stood up the website and then would go to shoe stores, take pictures of shoes, and post them up on the website. If somebody bought them, then he would go back to the store, buy the shoes, wrap them up, and send them to the customer himself. He didn’t have to set up the entire back-end logistics systems. His focus was testing peoples’ need for a nice way to buy shoes online.

I’m constantly writing down ideas in a big notebook that I have in Evernote – I have hundreds of ideas. Then, I like to think through the user personas and scenarios of use for the product. The persona helps you describe who the person is using your product; the scenario helps you describe the need for it and how they will use it.

Next, I begin producing a set of wireframes of what the user interface will look like for the product, often pen or pencil and paper hand sketches. In general, I’m very transparent about what I’m working on. I blog about it, I tell lots of people about it, I’m asking for feedback from anyone that might be interested in hearing about it.

Rather than worrying about someone “stealing” your idea, I’m of the opinion that you’re either the right one to bring a product to market or you’re not. After all, probably less than a third of the final product is due to some sort of novel inspiration. The majority of it, let’s say 70% or more, comes from the work and effort put into a lot of iterating until something great emerges.

I don’t have a particular philosophy or methodology for product design and development because my opinion is a specific product philosophy has the potential to make you too rigid and leave you closed to new ways of approaching a problem or experimenting with new ideas. So, I guess might say that my philosophy of product design is: don’t have a philosophy.

The very first thing I tell first-time founders is to “try to drown the baby” as early as possible.

By that, I mean: if you can kill your own idea really quickly – through some basic market research, or competitor research to determine if others have already tried it and failed, or some other form of objective review to ensure that it is rational – then you can save yourself a lot of time, money, and frustration.

Unfortunately, I find that too often, first-time founders skip this step or mostly ignore it, with the expectation that they can come back later to fix it. But, by then, it may be too late.

On the other hand, if you make a legitimate attempt to kill your idea – arguing all of the reasons why it won’t work, testing it with discerning customers, etc. – but it continues to live, then you know you may have something worth pursuing.

I went to law school with the purpose to “love people in a powerful way.” How that evolved was to help entrepreneurs work with what they have to be successful.

After getting my degree and working in industry, I left a large law firm to found my own law firm with the intent of representing and connecting innovators and investors. I founded the SKU accelerator in 2011, to further that purpose, specifically for consumer packaged goods (CPG), e.g., grocery items, personal products and dry goods.

My main advice to someone with an idea is to “make that idea” …physically create it by cooking, hammering, mixing, or stitching it to the point where you can test it.

A drawing or description isn’t sufficient: you have to produce enough of a real-world facsimile of it to see if it has any ability to take flight, to get off the ground. Examples are a “taste test” sample of a recipe, a homemade prototype of a handbag, etc.

While we schedule a lot of time to host free meetings and coffees with people who have an idea and are looking for a way to get started, the SKU accelerator is for companies with a proven product, what we call market-validated.

So, before you come to SKU, you need to have a sample or prototype of your product and you must have some evidence demonstrating the results of people (i.e., your target customers) having a personal experience with your product.

At first, the highest priority is to spend enough time working with your product to make the experience good. You need to achieve a baseline of success at every stage, satisfying your customers and meeting their needs at an appropriate level of volume and quality.

For example, if I’m creating a food product, after first trying it with friends and family, I would then go to the local farmer’s market to see how the product does there.

After that, I would try to introduce the product through a local retail grocer that features local foods and whose shoppers patronize and support them. Again, elevate the baseline of satisfying your customers and meeting their needs at each stage.

First-time entrepreneurs can tend to be pretty set in their way and get very tunnel-visioned. They don’t want to deviate from their product vision, because they are so passionate about it – it’s why they are doing what they do. So, I generally encourage them to go out and fail.

But, I always suggest they narrow down their idea to a very, very small piece of what they want to accomplish and then try that first. If it fails, then they haven’t lost much; they can learn from their mistakes and then keep going. If it succeeds, then they can quickly move on to the next thing.

As your organization grows, it’s important to start establishing structure – not necessarily to allow for a flatter organization – but to allow product and service innovative ideas to surface, from the intern through to the COO.

This is an important step early on, because employees tend to constantly take their ideas to various members of the leadership team. This causes chaos since there isn’t a methodology to effectively capture and vet new concepts, and determine whether or not the organization should act upon them.

Here’s a great example of a simple tool that delivers powerful results. Create a shareable spreadsheet or document (e.g., using Google Docs) where people can describe their ideas, categorized by what the leadership team has determined are the main drivers of the business.

These categories could be very different, depending on what industry the business is in. For example, a manufacturing company’s drivers could be quite different than those of a tech services business. The description of the idea should succinctly overview salient details, such as:

- Concept

- Proposed Market Test

- Estimated Investment (Time and Resources)

- Expected ROI

- Drivers (i.e., Brand Equity, Customer Acquisition, Average Order Value, etc.)

- Enablers (i.e., Human Resources, Skills, Infrastructure, etc.)

- Etc.

This tool provides a construct that enables people to provide input. Everyone knows they can use; it doesn’t matter who you are — with the result being a greater, shared sense of personal empowerment.

It also provides a way to build idea generation into whatever the product or service development roadmap is. The roadmap clearly will have its own cadence and needs, depending on customer requirements. But, the tool can be worked in at scheduled points that make sense for the roadmap — it could be quarterly, it could be monthly, depending on how young the company is and how fast the iterations are.

The ideal process is to have a review team, with executive and other senior leadership team participation, sit in on all of the reviews. Each person with an idea gets the same allotment of time to pitch it – approximately 5 minutes, with time set aside for questions and summation.

During the pitches, no feedback should be provided on the ideas. After all of the ideas have been heard, the review team organizes them by priorities and, for each idea, score it in a 2x2 table of low or high VALUE on one axis, with low or high EFFORT on the other axis.

The low value-high effort ideas automatically get knocked out. More than likely, the same is true for the low value-low effort ideas, although in some cases, they may get put on the list to do, because they are minimal distraction and are a passion project for someone.

The high value-low effort ideas get automatically advanced for a final review. The high value-high effort ideas are the ones where the majority of discussion is likely to occur among the leadership team. In these situations, one means of advancing the idea towards action is to seek a business plan or at least a more robust workplan describing how the idea would be produced.

It’s important to note that if an idea from this process gets advanced to the product roadmap, then, more than likely, something else that was on the roadmap must come off of it, or at least be de-prioritized. No company has unlimited resources and, thus, there is a clarity and, in a sense, ruthlessness that such rigor brings to product roadmap decision-making.

By following this process, the low-value ideas at least receive feedback, providing rationale for why they weren’t pursued. But, if the team members that came forward with the idea are encouraged to “take another kick at the can” and come back with an adjusted, more impressive pitch, then there is a sense of fairness and a belief that there is genuine desire to get the best results from everyone in the company.

I find companies are far better off if they put something like this in place early. Otherwise, if and when they grow rapidly, suddenly management finds themselves inundated with ideas – from the ill-considered to the stellar – with no way to prioritize or vet them.

In summary, this construct is somewhat a modern-day, digital turn on the historical suggestion box, with rigor and transparency around it. The beauty is that it allows for serendipity to occur in the product development life cycle and it is a relatively light-weight process to adopt.

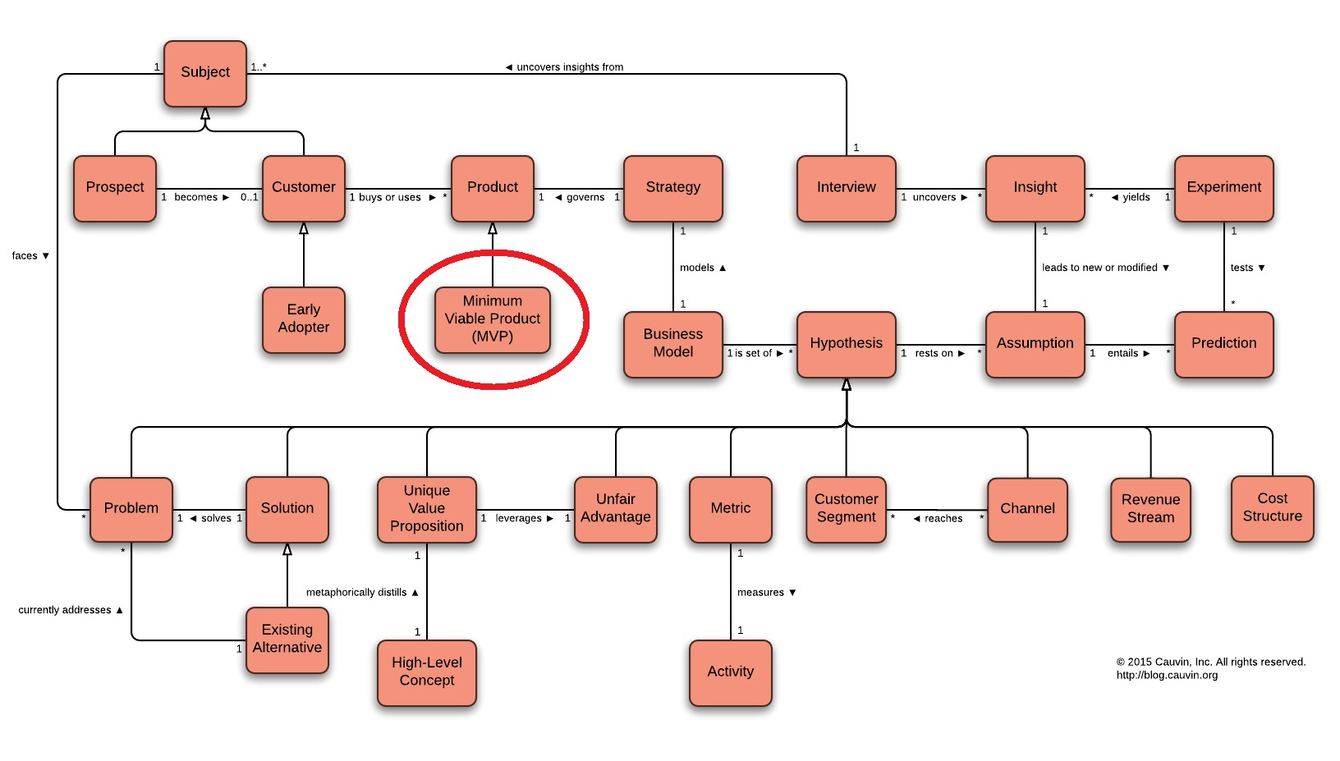

The lean startup movement popularized the term "minimum viable product". The purpose of a minimum viable product (MVP) is to focus our efforts on just those that yield the most return for our investments of time, effort, and money. Yet definitions of what qualifies as an MVP vary.

Some practitioners consider an MVP a minimum experiment we can run to learn or to test an aspect of our product strategy. In this view, our MVP might be a landing page that expresses the unique value proposition (the component of the product strategy that represents the value we envision the product uniquely delivering to customers) and enables prospective future users to sign up for an announcement when the product is ready. From the number of signups, we can gauge whether our hypotheses - the unique value proposition, the target market, and the channels we use to reach them - are flawed or potentially have merit.

A more ambitious - and arguably more popular - view of a minimum viable product is a more "complete" product that actually delivers the promised unique value. When we initially create a lean canvas (one-page document describing our product strategy or "business model" hypotheses), the product we're describing is an MVP.

The differences between these two definitions of "minimum viable product" are largely academic. We typically perform both activities: we define our hypothetical minimum product that will uniquely deliver value, and we run experiments to test the underlying hypotheses and assumptions. In either case, we iteratively test our hypotheses and adjust them as we falsify them or make new discoveries. These experiments culminate in putting the implemented MVP in front of customers, determining whether they buy it, and determining whether they truly derive value from it.

By taking this approach, we've taken the "leanest" path to learning and creating value. To reach a "whole" product beyond the MVP, we continue to experiment, measure, and learn, all the while iterating to a product and product strategy with the maximum potential to succeed in the marketplace.

In both the path to the MVP and the path from the MVP to a mature product, teams are wise to focus relentlessly on supporting the unique value proposition. We design and refine our unique value proposition to achieve our business goals, and we take into consideration almost all of the other factors (e.g. revenue potential, alignment with corporate strategy, feature requests) that we might be tempted to use to drive on-going product decisions. Our priorities should flow naturally from testing and realizing the unique value proposition; we risk ending up with a "Frankenstein product" (an incoherent product with a hodgepodge of features) if we set aside the unique value proposition and re-evaluate individual priorities in terms of the factors that already went into our design of the unique value proposition.